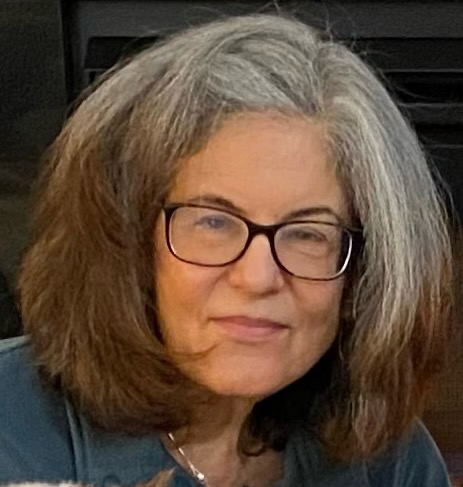

Jane "Q" walks down the hallway to her office, barely nodding to

her assistant as she closes the door. At her computer, she pulls up

a half-finished project and recalls

her distraction at lunch. Hopefully, the clients hadn't noticed.

At her computer, she pulls up

a half-finished project and recalls

her distraction at lunch. Hopefully, the clients hadn't noticed.

But what if they did?

She exhales audibly, eyeing the boxes in the corner of her office. Another late night. Is she going to make it at this place? Does she even care? For a long minute, before getting down to work, she imagines just walking away.

Life In The Boiler Room

Pressure, overwork, boredom, escape fantasies. Unfortunately, familiar topics to many professionals. And while it's important to be aware of demands that can make work feel like a straight-jacket, it's equally important not to hold the job liable for personal behavior patterns that have a history all their own. Sometimes it's easier to seek refuge in the darker aspects of our professions than face our own fears and vulnerabilities.Jane was doing that. In her initial sessions, she was convinced that it was her job--the deadlines, the politics, the pressure, the personalities. She told me about a similar experience at another office. We explored her anxiety and depression from that perspective, specifically, that work was the problem. Still no relief. Jane's symptoms persisted. She continued to monitor everyone's tone and facial expression for the least sign of trouble and found little pleasure at the office regardless of how well she performed.

Jane wasn't able to see it at first, but something had left its imprint and kept her responding in a certain way--a way that was self-defeating, but one that she knew and faithfully repeated day after day, effortlessly, mindlessly.

"Why Can't I Seem to Learn from Experience"

The concept of psychological templates distorting our present day experience has made sense to clinicians for years. Now the current stream of scientific research takes us further, showing that the "wetware" of the human brain contains mechanisms that allow neuronal connections to shift and change. This "rewirability" is basic to all learning, including un-learning patterns of behavior and thought in psychotherapy.So why are the changes so hard?

Because most people arrive for therapy in a state of ambivalence. There's the conscious: "I definitely

want to reduce my stress levels" versus the unconscious "but not if we have to explore that!" The therapist must push through this wall of resistance so

characteristic defensive maneuvers can

be identified and given up. Once Jane Q. was able to get past her particular defenses, her symptoms disappeared. And though Jane's

situation is unique, many of us can easily identify with her confusion and inability to get things right. Who hasn't been on auto-pilot,

invoking attitudes, positions, strategies, and behaviors simply because they are familiar?

characteristic defensive maneuvers can

be identified and given up. Once Jane Q. was able to get past her particular defenses, her symptoms disappeared. And though Jane's

situation is unique, many of us can easily identify with her confusion and inability to get things right. Who hasn't been on auto-pilot,

invoking attitudes, positions, strategies, and behaviors simply because they are familiar?

Many dissatisfied professionals feel imprisoned in a suit of character armor: "I've always been this way. What's the use?" But what is "character" other than a product of past and present choices? To decide that we are somehow stuck where we are is to ignore the fluidity of the human personality or worse, to confuse one's defenses with one's essence. If you are an ambivalent professional--feeling the conflict between avoidance or denial on the one hand and the wish to improve on the other--you may want to ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I scapegoating my work by projecting my own

shortcomings onto it? Rather than tackling my limitations head-on,

do I avoid them by bad-mouthing my career?

- Is my work really so depressing? Or have I always been somewhat depressed? Similarly, is my work really so stressful, or have I always been a worrier? Moody? Quick to anger? Withdrawn? Critical? Controlling? A procrastinator? Am I right to suppose that things would be different in another job? In another field? Or would I drag my problems with me into the next position?

- If the problem lies with me, how ready am I to

make a change? Would I be willing to consider looking at the ways

that I handle confrontation and anger? Disappointment and sadness?

Closeness and intimacy?

Reality tells us that our problems and dissatisfactions are a mixture of both external and internal factors. Reality also tells us that although change is uncomfortable, it is not impossible. Honest introspection cannot provide the keys to the kingdom, but it can better equip us to make critical distinctions between internal and external, past and present. Without the ability to make such distinctions, we may be condemned to a life of avoidance and finger-pointing, never being sure we've managed to identify the real culprit.